Defining Burnout

The term "burnout" has been a buzz word lately. So many of us have lived through the interconnection between work, physical health, and mental health. But what is burnout, how does it present, and what can we do about it?

The World Health Organization defines burnout as a "syndrome," or cluster of symptoms, "resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed." Several models exist for measuring burnout, ranging from one-dimensional exhaustion models to four-dimensional models measuring enthusiasm, psychological fatigue, avoidance, and guilt.

Colloquially, many consider burnout to be work-related exhaustion connected to working too many hours — hence, we often encourage people to take time off. While overwork does comprise a vital element to all burnout models, fatigue from too many hours on the job does not define burnout. As taking time off can be restoring, but it will not fix your burnout if the workplace you are going back to hasn't addressed the root cause.

According to the Maslach Burnout Inventory, burnout is characterized by:

Exhaustion: Ongoing physical, mental, and emotional fatigue that extends beyond what a good night's sleep can fix. This level of exhaustion is deep in the soul.

Cynicism: Indifference and negativity toward work, school, or other stressors. Often manifests as a lack of joy or blaming others for mediocre performance. The world is seen through “rust colored glasses.”

Impaired professional efficacy: Not feeling accomplished due to lack of reward, recognition, or validation. Often people can feel helpless to enact change.

At work, burnout stems not only from an overload of responsibilities but from risk factors such as effort-reward imbalance, lack of autonomy, incongruent values between an individual and their workplace, inequitable treatment, and poor colleague-superior relationships.

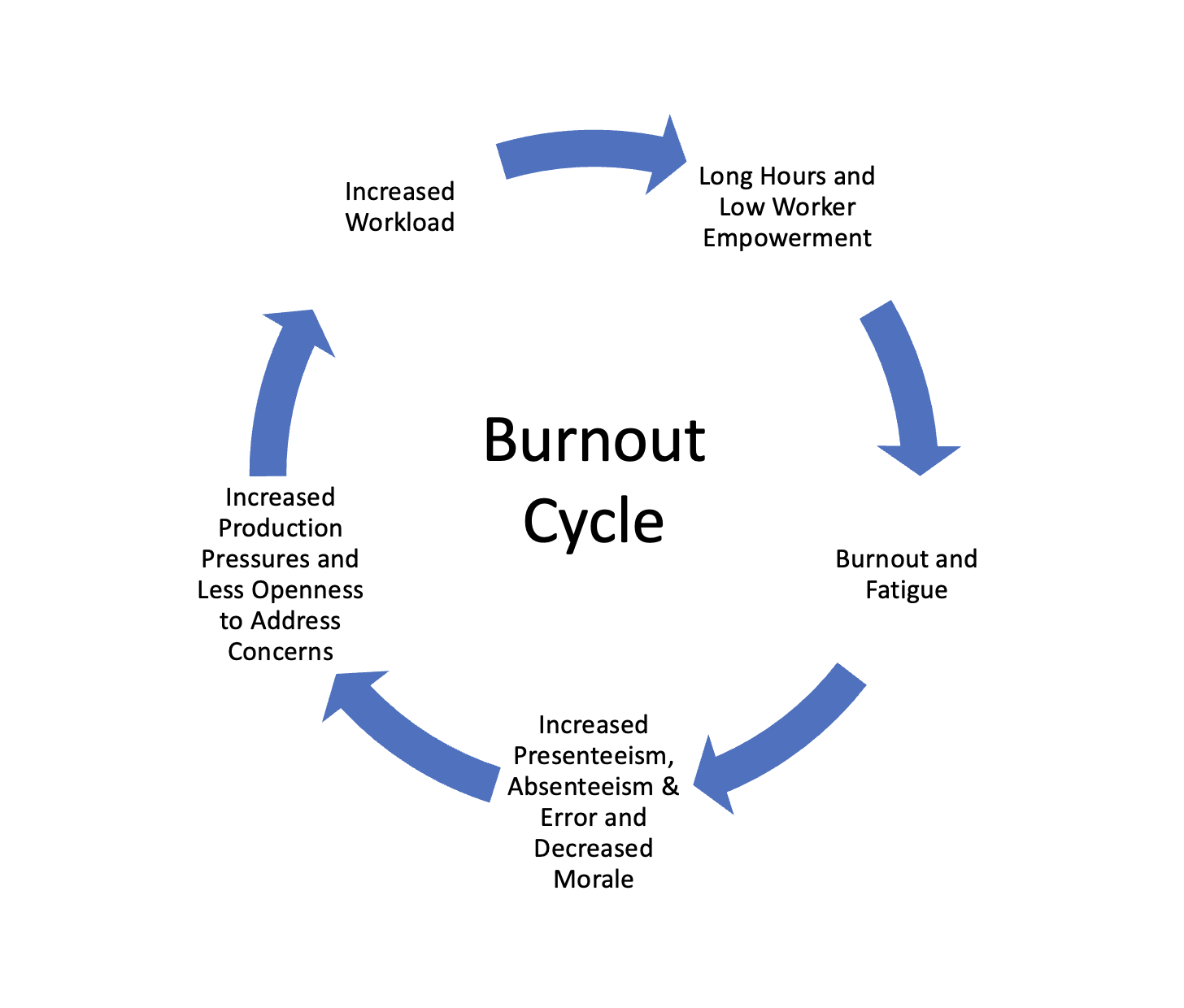

When we have these “psychosocial hazards” at work, many people feel compelled to push themselves to burnout because they fear that, if you don't push yourself past the breaking point, somebody else will. Thus, the “Burnout Cycle” becomes vicious. Long hours lead to fatigue lead to disengagement leads to increased pressure leads to increased workload and on it goes.

The Spread of Burnout

The effects of burnout extend far beyond one personal bubble. For one thing, because it relates so strongly to interpersonal conflicts and aggressive environments, it can spread through the negative social interactions that burnout can both originate from and cause. Whole communities can move from engaged and inspired to totally detached, pessimistic and deflated.

Additionally, poor health and burnout are good pals. Muscle pain and depression prove exceedingly common among people with burnout. Many also suffer from headaches, high blood pressure, a weakened immune system, gastrointestinal distress, sleep problems, and even substance use disorders. Up to 90 percent of people with severe burnout—those who experience daily symptoms—also suffer co-occuring pain, psychiatric, and other conditions.

Burnout doesn't just stress your mind and limbs—it can also stress your heart. Research[1] indicates that, among industrial workers, an increased burnout inventory score predicted a jump in the risk of future hospitalization for both cardiovascular and mental health incidents.

Is Burnout the Same as Depression?

Depression tends to co-occur with burnout. For some, depression is a result of the chronic stress of burnout. Lifestyle factors such as infrequent exercise, poor nutrition, and inadequate sleep resulting from burnout can aggravate depressive disorders and vice versa. Both are chronic conditions with psychosomatic elements. However, while the two often tango, burnout and depression are indeed distinct.

Depression's causes remain more complex than can be explained in a paragraph and run deeper than extrinsic factors like work. Depressive disorders primarily stem from a combination of risky genes, environments, experiences, and personality traits that—together—predispose someone to excessive guilt, feelings of worthlessness, fatigue, dulled senses, slowed cognition and movement, rumination, and even self-harm. While external circumstances can contribute to the severity or trigger the onset of a depressive disorder, depression can exist without a tangible "root."

Burnout, on the other hand, is defined almost entirely by one's relationship to the external world and only occurs in response to an explicit, chronic stressor or stressors. The scope of cynicism and inefficacy is limited, at least at first, toward work itself. Psychology Today writer, MacKenzie Littledale posted, burnout occurs because "the work we once enjoyed is joyless, thankless, and even pointless," whereas "depression makes life itself pointless" (emphasis added).

What Can You Do?

Now that we’ve clarified burnout and its effects, what can we do to alleviate it? In part two of this series, we’ll detail a multifaceted strategy to mitigating burnout that embraces both private and institutional change.

A special thank you to the guest panelists who participated in the #ElevateTheConvo Twitter chat on October 28, 2021, hosted by Dr. Sally Spencer-Thomas. This post is based on the contributions of the following individuals:

Dr. Camila Pulgar, @DrCamilaPulgar

Susan J. Farese, RN @sjfcommo

CRNP Angel V. Shannon, @angelvshannon

Al Levin, Educator, @allevin18

Evan Whitehead, Educator: @EvanWhitehead00

Charles A. Francis from the Mindfulness Meditation Institute, @TrainingMindful

Barry Bradford, Spiritual Leader, @BarryMotivates

Jordan Brown, Advocate, @JPBrown5

[1] Toppinen-Tanner, S., et al (2009). Burnout predicts hospitalization for mental and cardiovascular disorders: 10-year prospective results from industrial sector. Stress & Health, https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.1282